Nothing in Supergiant Games’ Pyre looks familiar. Set in a vast wasteland called the Downside, the world stretches outward for what seems an infinity. A strange geography of brightly coloured hills, swamps, and mountains is revealed bit by bit throughout the game’s opening hours, new screens charting the topography of a land whose history and culture is, at first, illegible.

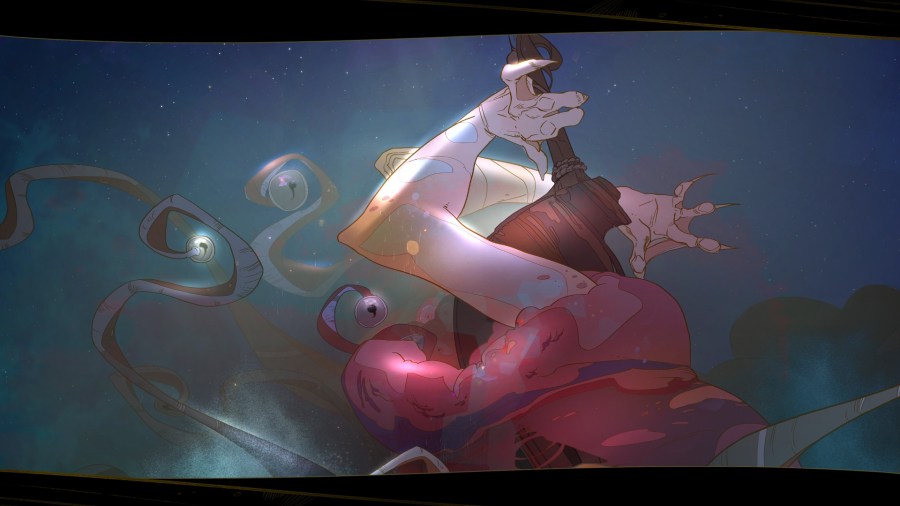

Pyre is fantasy of the truest sort. In place of the Western European mythology and pseudo-Dark Ages architecture that defines so much of the genre, it draws instead from a less familiar well. There are no stony castle towns or villages full of thatch-roofed, wattle and daub homes. The land is filled instead with organic-looking structures—bridges and shrines constructed from the bones of long-dead giants and occasional houses thrown together from piles of fungus or sculpted into the sides of rock formations like an otherworldly version of the carved cliffs of Jordan’s lost city of Petra.

Grounds the vastness of a fantasy world through the pages of a book

The result is a setting that encapsulates the game’s fiction—vast and unknowable, almost entirely divorced from the markers of the world we inhabit. As is to be expected, much of its first act is a process of trying to find reference points to hang onto. Pyre’s visuals echo in its writing, the mystery of its landscape paired by dialogue filled with mentions of bizarre proper nouns (the “Celestial Orb,” “Sung-Gries,” “The Empire of Sahr,” “The Plan,” and more ) that describe people, history, and locations that are impossible to make sense of until the plot ends up providing context.

The player, cast as invisible protagonist the Reader, is as unfamiliar with the Downside as the character she guides. Pyre is well aware of its fiction’s density, though. It’s most common aesthetic reference is a book, and, fittingly, each line of character dialogue scrolls past to the sound of a busy pen on paper. The kind of nouns mentioned above are displayed in a bold red and display a brief paragraph of expository detail (that often furthers confusion more than it explains) when the cursor hovers above.

Gigantic buildings studded with symbols whose power belongs to a culture so unlike our own that understanding it fully seems impossible

The overwhelming strangeness of Pyre presents a unique problem for its creators. The floating appendices mentioned above do little to provide an entryway for the audience, but, still, the game ends up gaining clarity as the plot progresses. Part of this is due to seeing characters, species, and landmarks during the character’s journey across the Downside, reducing unfamiliarity by matching the appearance of something with its name. The larger reason, though, is Pyre’s framing, which grounds the vastness of a fantasy world through the pages of a book—a format that not only functions as a reminder of the godly power of literacy for the game’s characters (in it, as in Christianity, the Word is creation) but provides a clear point of reference to an object and storytelling method familiar to players.

The book displays the world two pages at a time. Characters speak through it, each line of dialogue appearing on yellowed paper stamped with a red wax seal. The world, busy as it may be with the blinding technicolour details of its swamps, ice fields, and rocky deserts, is made legible through scraps of paper that appear on corners to prompt further exploration. Most obviously, all of Pyre’s training battlefields are made up of characters running across the pages of an open book, arena edges bordered by sheaves of thick-cut paper on all visible sides.

The sense is of a space, enormous and alien as it may be, that can be made sense of page by page. Paper filled with colour, though bursting with both image and sound as often as words, is something all audiences can comprehend. We can work with the immensity of the strangest concepts if written clearly. Pyre’s book functions as a porthole looking out across an ocean. It narrows the broad viewpoint of a fantasy world into smaller segments that can be compartmentalized and, over time, expanded in relation with one another until the larger whole is revealed. Bit by bit, everything becomes clear.

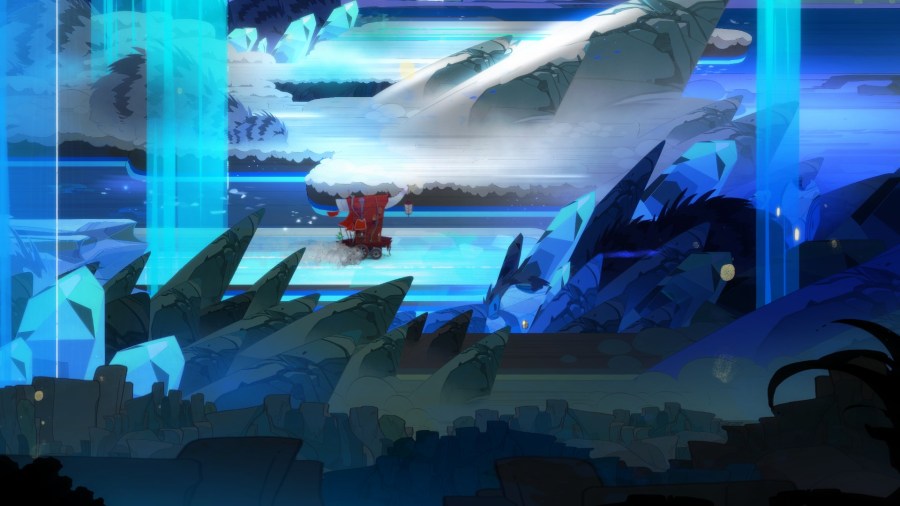

Pyre’s story is structured as a journey. Its characters travel the Downside in a rickety wooden caravan capable of driving, flying, and boating across the landscape on its way between ceremonial, football-style tournament matches whose location and meaning is quite literally ordained by the stars above. As it crisscrosses the Downside, the cart is constantly dwarfed by the environment and its architecture. It’s nearly swallowed by crashing waves when sailing an ocean or trees as it passes through a dense forest, and appears insignificant against the backdrop of gigantic buildings studded with symbols whose power belongs to a culture so unlike our own that understanding it fully seems impossible.

The book displays the world two pages at a time

The caravan is a kind of metaphor for the audience’s relationship to meaning in Pyre—and any work of fiction willing to depart so fully from references to the world we know. Its journey across the Downside renders it small, but its humble size is also the grounding through which we can centre a trip into mysteries large enough that they can’t be grasped all at once. Like the caravan, players grab onto what points of familiarity the story makes available. We cling to the book and give ourselves over to the game, trusting in its creators to show what needs to be shown of a vast and unknowable space.

Pyre’s success, then, is in how fully it realizes the fantastic. Its art is stunning not only because of its detail and imagination, but also because it hints always at an entire reality divorced from our own, with its own architecture, structures and spaces. Creating fiction so strange and vast is impressive for its own sake. Finding novel ways to ensure the audience can appreciate its breadth without becoming entirely lost in confusion is another challenge entirely, and one that Pyre manages to solve with a delicate, nuanced touch.

If you enjoyed this study please consider supporting the Heterotopias project through purchasing our zine. Issues 001 + 002, featuring almost 200 pages of visual studies and critical essays on games and architecture, are currently available in our summer sale here.

Thank you for your support!

Nothing in Supergiant Games’ Pyre looks familiar. Set in a vast wasteland called the Downside, the world stretches outward for what seems an infinity. A strange geography of brightly coloured hills, swamps, and mountains is revealed bit by bit throughout the game’s opening hours, new screens charting the topography of a land whose history and culture is, at first, illegible.

Pyre is fantasy of the truest sort. In place of the Western European mythology and pseudo-Dark Ages architecture that defines so much of the genre, it draws instead from a less familiar well. There are no stony castle towns or villages full of thatch-roofed, wattle and daub homes. The land is filled instead with organic-looking structures—bridges and shrines constructed from the bones of long-dead giants and occasional houses thrown together from piles of fungus or sculpted into the sides of rock formations like an otherworldly version of the carved cliffs of Jordan’s lost city of Petra.

The result is a setting that encapsulates the game’s fiction—vast and unknowable, almost entirely divorced from the markers of the world we inhabit. As is to be expected, much of its first act is a process of trying to find reference points to hang onto. Pyre’s visuals echo in its writing, the mystery of its landscape paired by dialogue filled with mentions of bizarre proper nouns (the “Celestial Orb,” “Sung-Gries,” “The Empire of Sahr,” “The Plan,” and more ) that describe people, history, and locations that are impossible to make sense of until the plot ends up providing context.

The player, cast as invisible protagonist the Reader, is as unfamiliar with the Downside as the character she guides. Pyre is well aware of its fiction’s density, though. It’s most common aesthetic reference is a book, and, fittingly, each line of character dialogue scrolls past to the sound of a busy pen on paper. The kind of nouns mentioned above are displayed in a bold red and display a brief paragraph of expository detail (that often furthers confusion more than it explains) when the cursor hovers above.

The overwhelming strangeness of Pyre presents a unique problem for its creators. The floating appendices mentioned above do little to provide an entryway for the audience, but, still, the game ends up gaining clarity as the plot progresses. Part of this is due to seeing characters, species, and landmarks during the character’s journey across the Downside, reducing unfamiliarity by matching the appearance of something with its name. The larger reason, though, is Pyre’s framing, which grounds the vastness of a fantasy world through the pages of a book—a format that not only functions as a reminder of the godly power of literacy for the game’s characters (in it, as in Christianity, the Word is creation) but provides a clear point of reference to an object and storytelling method familiar to players.

The book displays the world two pages at a time. Characters speak through it, each line of dialogue appearing on yellowed paper stamped with a red wax seal. The world, busy as it may be with the blinding technicolour details of its swamps, ice fields, and rocky deserts, is made legible through scraps of paper that appear on corners to prompt further exploration. Most obviously, all of Pyre’s training battlefields are made up of characters running across the pages of an open book, arena edges bordered by sheaves of thick-cut paper on all visible sides.

The sense is of a space, enormous and alien as it may be, that can be made sense of page by page. Paper filled with colour, though bursting with both image and sound as often as words, is something all audiences can comprehend. We can work with the immensity of the strangest concepts if written clearly. Pyre’s book functions as a porthole looking out across an ocean. It narrows the broad viewpoint of a fantasy world into smaller segments that can be compartmentalized and, over time, expanded in relation with one another until the larger whole is revealed. Bit by bit, everything becomes clear.

Pyre’s story is structured as a journey. Its characters travel the Downside in a rickety wooden caravan capable of driving, flying, and boating across the landscape on its way between ceremonial, football-style tournament matches whose location and meaning is quite literally ordained by the stars above. As it crisscrosses the Downside, the cart is constantly dwarfed by the environment and its architecture. It’s nearly swallowed by crashing waves when sailing an ocean or trees as it passes through a dense forest, and appears insignificant against the backdrop of gigantic buildings studded with symbols whose power belongs to a culture so unlike our own that understanding it fully seems impossible.

The caravan is a kind of metaphor for the audience’s relationship to meaning in Pyre—and any work of fiction willing to depart so fully from references to the world we know. Its journey across the Downside renders it small, but its humble size is also the grounding through which we can centre a trip into mysteries large enough that they can’t be grasped all at once. Like the caravan, players grab onto what points of familiarity the story makes available. We cling to the book and give ourselves over to the game, trusting in its creators to show what needs to be shown of a vast and unknowable space.

Pyre’s success, then, is in how fully it realizes the fantastic. Its art is stunning not only because of its detail and imagination, but also because it hints always at an entire reality divorced from our own, with its own architecture, structures and spaces. Creating fiction so strange and vast is impressive for its own sake. Finding novel ways to ensure the audience can appreciate its breadth without becoming entirely lost in confusion is another challenge entirely, and one that Pyre manages to solve with a delicate, nuanced touch.

If you enjoyed this study please consider supporting the Heterotopias project through purchasing our zine. Issues 001 + 002, featuring almost 200 pages of visual studies and critical essays on games and architecture, are currently available in our summer sale here.

Thank you for your support!

Share this: