Every cyberpunk story, great or otherwise, is defined through the language of urban spaces. Were we to draft a composite sketch of the genre’s ethos; that image would inevitably be of a metropolis.

Already the word cyberpunk summons dystopic visions of urbanity: rain-slicked pockmarks on stygian asphalt swelling with toxified waste water, their surface reflecting the phosphorescent glow of neon signage; sigils searing through the dark like a brand upon the skin. Obelisks of mirrored glass and concrete plunging whole populations into perpetual darkness. The concepts of ‘night’ and ‘day’ so indeterminate as to be irrelevant; Its denizens, a faceless transient mass. All these images, siphoned through the refracting lens of the genre’s most enduring locales; the alleys of William Gibson’s Chiba, the slums of Mamoru Oshii’s Niihama, the corporate citadels of Ridley Scott’s Los Angeles. Of this we can be certain: the first, last, and greatest protagonist of cyberpunk is no “console cowboy”, but the city itself.

A future envisioned through the mirage of the present

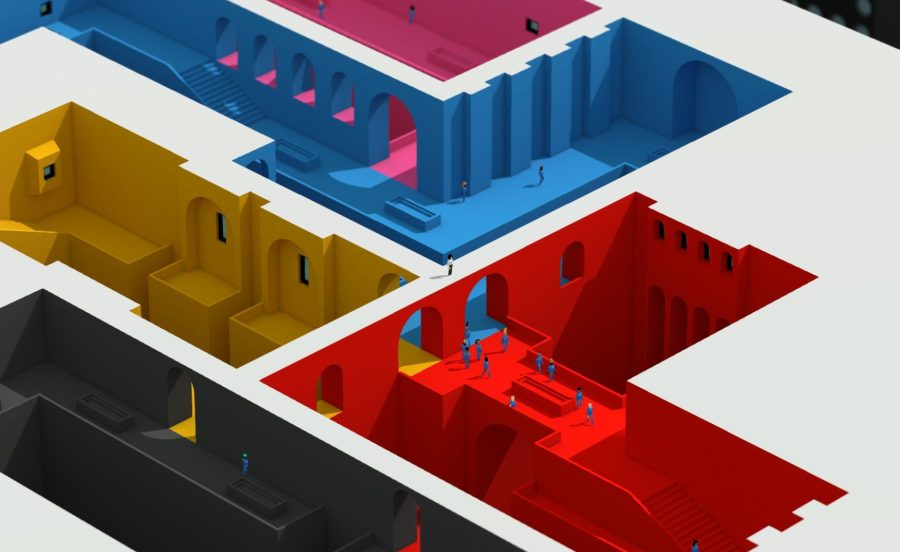

Tokyo 42 understands this intuitively, its isometric perspective situating the genre’s debt to the lineage of modern architecture at the forefront of the player’s perspective. We are infinitesimal; avatars milling about the circuitry of urban design, anthropomorphic iotas swallowed by the sprawl of post-modernity. Compared to its enormity and scope, we are never as interesting or as important as the world around us. What havoc we wreak, what change we affect, amounts to as little as a blip in the city’s ever-changing ecosystem. Our characters may live, die, and live again, but only the city is forever.

Japan has long earned its reputation as a nexus for architectural adventurism. Every sufficiently-advanced country embraces, to some extent, an aesthetic and cultural plurality through the shaping of its architectural identity, though the conditions attributable to Japan’s case are particularly fascinating. By the end of World War II, the Allies’ coordinated bombing runs had decimated over a third of Japan’s housing stock, with nearly eighty-five percent of buildings in some cities being totally destroyed. The country’s industrial resurrection in the 1950’s coincided with a migration of citizens from Japan’s agrarian fringes back to its urban epicenters. Buoyed by an exponential wave of manufacturing exports, flush with cash, and facing a nascent housing crisis brought about by a spike in birth-rates, Japan’s laissez-faire zoning laws regarding residential space paved the way for the country’s transformation into a crucible for avant-garde architecture; A sentiment founded in the interest of nurturing and incentivizing more creative, dynamic, and affordable approaches to housing. Out of this architectural zenith, the Metabolist movement was born.

An ecology of variable, ready-made apartments that would regularly trade capsules across the city; a utopian architectural equilibrium that prioritized functionality alongside aesthetics

Founded during the 1960 Tokyo World Design Conference by Kenzo Tange and an aspiring group of young designers and architects, Metabolism was an architectural philosophy that sought to integrate technology, radical utopian ideals, and organic expressionism to usher forth a then-new paradigm in housing and industry. Metabolism was Japan’s answer to Brutalism, which at the time had recently come into prominence across the U.K. and United States. Both styles were defined through their respective synthesis of opposing forces. Brutalism sought to juxtapose the primitivity of the past with the sophistication of the would-be future, while Metabolism was a cultivation of the organic from out of the inorganic. Of the movement’s founding participants, Kisho Kurokawa was a central figure in Metabolism’s rise to notoriety not only for his part in its founding, but for crafting its most enduring architectural testament, the Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Following an impromptu police chase complete with requisite parkour finale, Tokyo 42 begins with our character being involuntarily enlisted as a hired assassin-cum-freedom fighter in a resistance movement waging a shadow war against a nefarious mega-corporation. All in all, a fairly boilerplate premise for the genre, though admittedly little more than a pretense by which to send us ricocheting across the far and many corners of the game’s incarnation of an escapist ‘Neo-Tokyo’. Our first contract is to procure a pistol from an adjacent apartment complex and dispense with a golf tycoon. To the layperson, this structure is little more than one of countless other vaguely futuristic locales which populate the city. To an architecture aficionado however, it’s likeness is unmistakable; a not-so-subtle facsimile of Kurokawa’s Capsule Tower. What at first seems an innocuous nod to an architectural curiosity is later revealed to be its guiding vector. Of all the styles perpetuated throughout Tokyo 42, whether intentional or inadvertent, Kurokawa’s masterpiece is the game’s most recurrent motif.

When it was completed in 1972, the Capsule Tower stunned the architectural world, earning praise as one of the most audacious projects realized in that year and the most consummate vindication of the Metabolists’ efforts yet. A thirteen-floor residential and office space, the Capsule Tower’s defining namesake was its 140 prefabricated capsule pods, whose cubic dimensions and circular portholes appeared at once both defiantly spartan and undeniably futuristic. A beehive by way of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Channeling the zeitgeist of the country’s newfound infatuation with technology, the Tower was designed to emulate the interchangability of a computer case, with each capsule in theory built to be routinely removed, repaired, and reinserted as needed. The dream, such as it was, was for Metabolism to spark an ecology of variable, ready-made apartments that would regularly trade capsules across the city; a utopian architectural equilibrium that prioritized functionality alongside aesthetics. That dream, however, was not to be.

Metabolism was a cultivation of the organic from out of the inorganic

It was the 1973 oil crisis that marked the beginning of the Japan’s economic downturn, stymieing the Metabolists’ momentum before stalling completely. In the wake of Japan’s late-century recession dubbed ‘The Lost Decade’, the Nakagin Capsule Tower had fallen into severe disrepair, at one point having been slated for complete demolition in 2007 before the international financial crisis of that year put a halt to these plans, ‘saving’ the building indefinitely. The Capsule Tower stands today as a landmark for urban explorers and squatters, a derelict relic of a bygone vision of the future, suspended in the amber of bureaucratic blindsight. How apt then, that the rise and fall into dilapidation of Kurokawa’s Tower would serve as an inadvertent analog for the cultural rise and intellectual stagnation of cyberpunk, itself a genre defined by its preoccupation with pan-asian aesthetics and architecture.

It seems inevitable, in hindsight, that cyberpunk would draw so heavily from Japan’s example. In the eighties, the country’s economic domination of the West seemed as much fact as it was fable, an incontestable certainty conjured from out of some ominous trending rumor. Japan’s manufacturing ascent, which manifested in part with the country’s wholesale acquisition of American auto plants, opposite that of the rise of home computing situated the country on the knife’s edge of the future, and the West took notice. Where else was William Gibson, a thirty-four year old science-fiction writer living in Vancouver, supposed to draw inspiration from? In an 1986 interview with Science Fiction Eye, Gibson expressed a retrospective embarrassment for his perfunctory grasp of Japanese geography while writing Neuromancer‘s setting, going so far as to describe his initial portrayal of a far-future Japan as, “[a type of] fantasy […] nineteenth-century Orientalia. Strange echoes, dreams from the West.” Gibson would elaborate on this nearly a decade later, when in an interview with Salon he stated that, while writing the entirety of Neuromancer and its sequels, he had never once himself set foot in Japan; His metropolitan vision of punk-refracted industrialism instead extrapolated from his observations of Vancouver, which at the time was and remains known for a sizeable population of Japanese tourists. Cyberpunk has always been framed through this initial context, a foreigner’s perspective as they marvel from afar at the idiosyncratic wonders of some yet unseen country; a future envisioned through the mirage of the present. Because of this, the genre’s primary texts have always toed the threshold between reverent speculation and fawning fetishization.

As it was with Gibson, so too it might seem at first glance for Sean and Maciek Strychalski, the fraternal development team behind Tokyo 42. While the former’s vantage point was British Columbia, the Strychalski brothers’ was a small flat in North London. However, there’s something distinct with regards to the brother’s approach to cyberpunk which distinguishes them from their spiritual forbearers. Listening to them speak, the first thing one might notice of them is the warmth and candor of their rapport; characteristics that inadvertently prove foundational to the game’s creation. “We wanted to approach it from a different angle than most other things have done before,” says Sean, Tokyo 42’s lead programmer. “Where [typical cyberpunk] worlds are dark and depressing, we wanted to show that corruption can also be in a light place.” Maciek, the game’s art director, echoes this sentiment. “In these futures that we see, it’s always set at night. But what about what happens in the day? It’s not there isn’t daytime in Tokyo, so that’s where we’re starting from. We’re trying to step away and trying to approach it from a slightly lighter, more colorful angle.” Having studied architecture in school, Maciek’s background was integral in honing the game’s aesthetic. Tokyo 42 is a confluence of multicultural influences. From the flying gondolas of Fifth Element to the Harley racers of Bōsōzoku bike culture, to the apocalyptic congestion of Kowloon Walled City and the serenity of Meiji-era temple shrines. But above all, the mark of Kenzo Tange and the Metabolists’ precedent is writ large across its stage. From Tange’s rendition of St. Mary’s Cathedral to Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, Metabolism and its descendents live on through Tokyo 42’s studious reincarnations.

Though while the old guard of cyberpunk have long since abandoned the term with its deterioration into pulp affectation, the Strychalski brothers have taken the genre up in open arms and given it a spit polish, imbuing it with an artificial exuberance that can come only out of the benevolent tyranny of Kawaii, all glossy pastels and leering woodland caricatures. The 1970 World’s Expo in Osaka is considered by historians as the first and last great hurrah of the Metabolists, an unfettered showcase of wild-eyed creativity the likes of which the world may never see again. But in Tokyo 42, the expo continues unabated, brave new worlds and adjacent possibilities made real through nothing more save a 60-degree turn of the camera.

If you enjoyed this study please consider supporting the Heterotopias project through purchasing our zine. Issues 001 + 002, featuring almost 200 pages of visual studies and critical essays on games and architecture, are currently available in a discounted launch bundle here.

Thank you for your support!

Every cyberpunk story, great or otherwise, is defined through the language of urban spaces. Were we to draft a composite sketch of the genre’s ethos; that image would inevitably be of a metropolis.

Already the word cyberpunk summons dystopic visions of urbanity: rain-slicked pockmarks on stygian asphalt swelling with toxified waste water, their surface reflecting the phosphorescent glow of neon signage; sigils searing through the dark like a brand upon the skin. Obelisks of mirrored glass and concrete plunging whole populations into perpetual darkness. The concepts of ‘night’ and ‘day’ so indeterminate as to be irrelevant; Its denizens, a faceless transient mass. All these images, siphoned through the refracting lens of the genre’s most enduring locales; the alleys of William Gibson’s Chiba, the slums of Mamoru Oshii’s Niihama, the corporate citadels of Ridley Scott’s Los Angeles. Of this we can be certain: the first, last, and greatest protagonist of cyberpunk is no “console cowboy”, but the city itself.

Tokyo 42 understands this intuitively, its isometric perspective situating the genre’s debt to the lineage of modern architecture at the forefront of the player’s perspective. We are infinitesimal; avatars milling about the circuitry of urban design, anthropomorphic iotas swallowed by the sprawl of post-modernity. Compared to its enormity and scope, we are never as interesting or as important as the world around us. What havoc we wreak, what change we affect, amounts to as little as a blip in the city’s ever-changing ecosystem. Our characters may live, die, and live again, but only the city is forever.

Japan has long earned its reputation as a nexus for architectural adventurism. Every sufficiently-advanced country embraces, to some extent, an aesthetic and cultural plurality through the shaping of its architectural identity, though the conditions attributable to Japan’s case are particularly fascinating. By the end of World War II, the Allies’ coordinated bombing runs had decimated over a third of Japan’s housing stock, with nearly eighty-five percent of buildings in some cities being totally destroyed. The country’s industrial resurrection in the 1950’s coincided with a migration of citizens from Japan’s agrarian fringes back to its urban epicenters. Buoyed by an exponential wave of manufacturing exports, flush with cash, and facing a nascent housing crisis brought about by a spike in birth-rates, Japan’s laissez-faire zoning laws regarding residential space paved the way for the country’s transformation into a crucible for avant-garde architecture; A sentiment founded in the interest of nurturing and incentivizing more creative, dynamic, and affordable approaches to housing. Out of this architectural zenith, the Metabolist movement was born.

Founded during the 1960 Tokyo World Design Conference by Kenzo Tange and an aspiring group of young designers and architects, Metabolism was an architectural philosophy that sought to integrate technology, radical utopian ideals, and organic expressionism to usher forth a then-new paradigm in housing and industry. Metabolism was Japan’s answer to Brutalism, which at the time had recently come into prominence across the U.K. and United States. Both styles were defined through their respective synthesis of opposing forces. Brutalism sought to juxtapose the primitivity of the past with the sophistication of the would-be future, while Metabolism was a cultivation of the organic from out of the inorganic. Of the movement’s founding participants, Kisho Kurokawa was a central figure in Metabolism’s rise to notoriety not only for his part in its founding, but for crafting its most enduring architectural testament, the Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Following an impromptu police chase complete with requisite parkour finale, Tokyo 42 begins with our character being involuntarily enlisted as a hired assassin-cum-freedom fighter in a resistance movement waging a shadow war against a nefarious mega-corporation. All in all, a fairly boilerplate premise for the genre, though admittedly little more than a pretense by which to send us ricocheting across the far and many corners of the game’s incarnation of an escapist ‘Neo-Tokyo’. Our first contract is to procure a pistol from an adjacent apartment complex and dispense with a golf tycoon. To the layperson, this structure is little more than one of countless other vaguely futuristic locales which populate the city. To an architecture aficionado however, it’s likeness is unmistakable; a not-so-subtle facsimile of Kurokawa’s Capsule Tower. What at first seems an innocuous nod to an architectural curiosity is later revealed to be its guiding vector. Of all the styles perpetuated throughout Tokyo 42, whether intentional or inadvertent, Kurokawa’s masterpiece is the game’s most recurrent motif.

When it was completed in 1972, the Capsule Tower stunned the architectural world, earning praise as one of the most audacious projects realized in that year and the most consummate vindication of the Metabolists’ efforts yet. A thirteen-floor residential and office space, the Capsule Tower’s defining namesake was its 140 prefabricated capsule pods, whose cubic dimensions and circular portholes appeared at once both defiantly spartan and undeniably futuristic. A beehive by way of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Channeling the zeitgeist of the country’s newfound infatuation with technology, the Tower was designed to emulate the interchangability of a computer case, with each capsule in theory built to be routinely removed, repaired, and reinserted as needed. The dream, such as it was, was for Metabolism to spark an ecology of variable, ready-made apartments that would regularly trade capsules across the city; a utopian architectural equilibrium that prioritized functionality alongside aesthetics. That dream, however, was not to be.

It was the 1973 oil crisis that marked the beginning of the Japan’s economic downturn, stymieing the Metabolists’ momentum before stalling completely. In the wake of Japan’s late-century recession dubbed ‘The Lost Decade’, the Nakagin Capsule Tower had fallen into severe disrepair, at one point having been slated for complete demolition in 2007 before the international financial crisis of that year put a halt to these plans, ‘saving’ the building indefinitely. The Capsule Tower stands today as a landmark for urban explorers and squatters, a derelict relic of a bygone vision of the future, suspended in the amber of bureaucratic blindsight. How apt then, that the rise and fall into dilapidation of Kurokawa’s Tower would serve as an inadvertent analog for the cultural rise and intellectual stagnation of cyberpunk, itself a genre defined by its preoccupation with pan-asian aesthetics and architecture.

It seems inevitable, in hindsight, that cyberpunk would draw so heavily from Japan’s example. In the eighties, the country’s economic domination of the West seemed as much fact as it was fable, an incontestable certainty conjured from out of some ominous trending rumor. Japan’s manufacturing ascent, which manifested in part with the country’s wholesale acquisition of American auto plants, opposite that of the rise of home computing situated the country on the knife’s edge of the future, and the West took notice. Where else was William Gibson, a thirty-four year old science-fiction writer living in Vancouver, supposed to draw inspiration from? In an 1986 interview with Science Fiction Eye, Gibson expressed a retrospective embarrassment for his perfunctory grasp of Japanese geography while writing Neuromancer‘s setting, going so far as to describe his initial portrayal of a far-future Japan as, “[a type of] fantasy […] nineteenth-century Orientalia. Strange echoes, dreams from the West.” Gibson would elaborate on this nearly a decade later, when in an interview with Salon he stated that, while writing the entirety of Neuromancer and its sequels, he had never once himself set foot in Japan; His metropolitan vision of punk-refracted industrialism instead extrapolated from his observations of Vancouver, which at the time was and remains known for a sizeable population of Japanese tourists. Cyberpunk has always been framed through this initial context, a foreigner’s perspective as they marvel from afar at the idiosyncratic wonders of some yet unseen country; a future envisioned through the mirage of the present. Because of this, the genre’s primary texts have always toed the threshold between reverent speculation and fawning fetishization.

As it was with Gibson, so too it might seem at first glance for Sean and Maciek Strychalski, the fraternal development team behind Tokyo 42. While the former’s vantage point was British Columbia, the Strychalski brothers’ was a small flat in North London. However, there’s something distinct with regards to the brother’s approach to cyberpunk which distinguishes them from their spiritual forbearers. Listening to them speak, the first thing one might notice of them is the warmth and candor of their rapport; characteristics that inadvertently prove foundational to the game’s creation. “We wanted to approach it from a different angle than most other things have done before,” says Sean, Tokyo 42’s lead programmer. “Where [typical cyberpunk] worlds are dark and depressing, we wanted to show that corruption can also be in a light place.” Maciek, the game’s art director, echoes this sentiment. “In these futures that we see, it’s always set at night. But what about what happens in the day? It’s not there isn’t daytime in Tokyo, so that’s where we’re starting from. We’re trying to step away and trying to approach it from a slightly lighter, more colorful angle.” Having studied architecture in school, Maciek’s background was integral in honing the game’s aesthetic. Tokyo 42 is a confluence of multicultural influences. From the flying gondolas of Fifth Element to the Harley racers of Bōsōzoku bike culture, to the apocalyptic congestion of Kowloon Walled City and the serenity of Meiji-era temple shrines. But above all, the mark of Kenzo Tange and the Metabolists’ precedent is writ large across its stage. From Tange’s rendition of St. Mary’s Cathedral to Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, Metabolism and its descendents live on through Tokyo 42’s studious reincarnations.

Though while the old guard of cyberpunk have long since abandoned the term with its deterioration into pulp affectation, the Strychalski brothers have taken the genre up in open arms and given it a spit polish, imbuing it with an artificial exuberance that can come only out of the benevolent tyranny of Kawaii, all glossy pastels and leering woodland caricatures. The 1970 World’s Expo in Osaka is considered by historians as the first and last great hurrah of the Metabolists, an unfettered showcase of wild-eyed creativity the likes of which the world may never see again. But in Tokyo 42, the expo continues unabated, brave new worlds and adjacent possibilities made real through nothing more save a 60-degree turn of the camera.

If you enjoyed this study please consider supporting the Heterotopias project through purchasing our zine. Issues 001 + 002, featuring almost 200 pages of visual studies and critical essays on games and architecture, are currently available in a discounted launch bundle here.

Thank you for your support!

Share this: